People first learning and building their identities occurs in their childhood homes. At home people discover behaviors gaining them currency and favor and develop personal assets fueling an expansion of their social self which readies them to wander out into the wild, weird world. Community is a first navigation and success of all types has contingency due to degrees of local homogeneity and their capacity for assimilation and/or elevation of status by meeting, exceeding local standards enabling one passage through.

This issue of Bookisshh examines works by two authors who examine and/or contend with identity. Michelle Zauner and Ling Ma explore external factors impacting, enhancing or impeding on a person’s identity and comfort therein whether alone, socializing, working on their career, or the more tender matter of tending to an ailing parent. Both authors send their characters on visits to homelands and readers are privileged in witnessing the experience of displacement, or worse ostracizing, when a person’s authenticity is challenged by cultural outsiders and insiders.

Readers, I challenge you to reader either with care or concern. We all belong and don’t belong at some time or another and we all have parents we love and unfortunately lose. Saying “Enjoy” seems flippant so I’ll part with “Consider.”

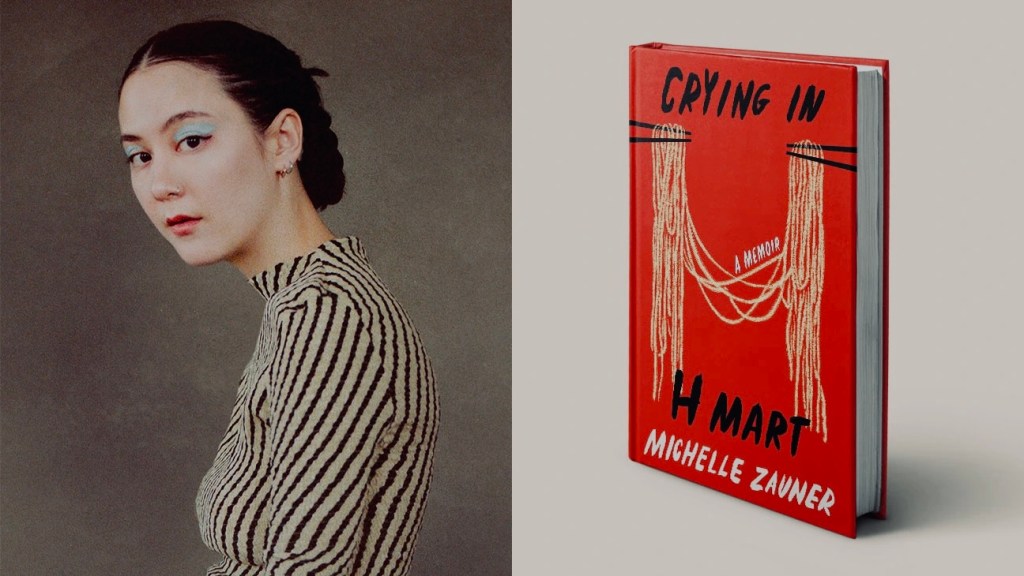

Crying In H Mart by Michelle Zauner / Memoir

In life it’s challenging to smoothly change hats when one wears too many hats… Author, Michelle Zauner adorns SEVERAL and two standout hats that center her narrative are being Korean and “white” (though it remains unclear what flavor of white— specifically the geographic and cultural origin of the paternal branch in her family). Zauner also juggles hats represented by musician, writer, cook, child, partner, business person and daughter, and it is the constant pressure to change or wear all hats that keep her coursing through the challenge of being confident and knowing herself while doing so many things especially tending to her ailing mother who is retreating more deeply into her Korean space.

Zauner is first generation on her Korean mother’s side and much of the cultural transmission that roots people in their culture of origin has been lost on Michelle. Michelle possesses some language skills mostly confided to parent/child intimacy and food. Food is where the narrative seeps deeply into readers and the emotional impact of food on memory and experience is parlayed through the granular descriptions of Michelle’s mother’s escalating cancer, her inability to prepare and enjoy food and Michelle’s desire to comfort and care for her mother using the cursory knowledge of authentic Korean food.

I’m not gonna sugar coat it for you—this is a painful read and I found myself having a cry here and there. The catharsis Zauner invites forward did not gut me per se, in fact it made me admire the beauty possible in caring for loved ones and knowing how/when to bring in support if it’s too difficult (though it doesn’t make it easier but space is granted to process one’s feelings on the matter). It is in these moments readers meet Korean sisters in immigration stories from near and far in her mother’s life. It is these sisters from the motherland that facilitate the dignity, silence and painful challenges that come with death and dying.

Zauner brings readers to Korea, California and other Asian countries to seek respite from her parent’s marriage problems, but readers experience is that there is no escape from history even in death and breakdowns happen that feel far more personal in faraway places too.

Death brings conclusion and in this work it’s a slow burn and a long simmer to that moment. I feel better reading this book. It reminds me to cherish the few things that are written on notecards that our family called tradition and I prepare from time to time. It also reminds me to accept what I know and don’t know about me and where I come from and to cherish the days with my mom that I have left with her.

Bliss Montage by Ling Ma / Short Story Collection

This collection of works interrogates aspects of life in dire need of change. Using the short story Ma looks at the experience of women in the institutions of marriage, family, academia and work and dramatizes the challenges and frustrations endured by women in this late moment of the world. Additionally, Ma points to the discriminations and stereotypes aimed toward Asian American Pacific Islanders both in the United States and to motherlands upon visit and/or hopeful return.

Structural themes Ma employs are the use of Frame Story in which a story is embedded within a story to unlock deeper meanings or bring attention to reference points and boundaries on behalf of reader, writer, character, setting, etc.. In this instance, Ma interconnects micro aggressions experienced both by women and women of Chinese heritage. Uniquely Ma brings forward that when it comes to “homeland” there is never a return once one has left because the past no longer exists in the presence and change is not transmitted to returnees and leaves them often feeling displaced which is a most painful discovery to endure when one is seeking to create family and connect traditions to experience a sense of wholeness.

Silent feminism guides female characters through living independently post marriage or just for the sake of their own choices BUT it’s never easy and women who choose independence for themselves are often viewed internally by culture as unfit or unwell. Regardless of the behaviors of husbands, boyfriends or bosses women’s lives are represented as contingent upon men even when they choose to live independently of men.

The standout story for me was during the MFA writing class during which degrees of cultural appropriation, racial stereotyping, and degrees of offensiveness occur during a class discussion on craft and authenticity. The finger pointing as should be was toward the emphasis placed on whiteness is dramatized in a crystal clear way though there is usually someone in the room who is non-marginalized who witnesses and agrees with the perspective of those who are persecuted and Ma didn’t make space for this person. While this is her right and perspective it makes me wonder: how many generations have to occur in order for everyone and no one in the room to matter and when will polarization as a basis of analyses evolve into something more pressing? Does culture, race and religion need to disappear completely in order for us to agree to disagree without conflict or legal provocation?

Ma’s creates detailed, meditative settings. It is very calming for readers to explore where cognitive complexity and emotional breakdown are occurring which is an interesting aspect in her prose. The worse things can happen but it’s very relaxing to read which neutralizes trauma and keeps readers dialed in and concerned.

Overall I liked the collection, but I feel like this book was a place card holder to keep Ma relevant until her next work comes forward. Likely this book should have come out before “Severance” so readers can experience the political, creative, and technical aspects of Ma’s writing. Ling Ma challenges the civilization we’ve nurtured in the Western world and makes us laugh at the capitalist by products Westerners work so hard for, covet and place their judgement on. Before you read, “Bliss Montage” consider “Severance” which I have graciously reviewed in previous editions of Bookisshh.

The thing that keeps me being a performer is my interest is society’s interest with identity, because I’m not sure that identity really exists. -Tilda Swinton