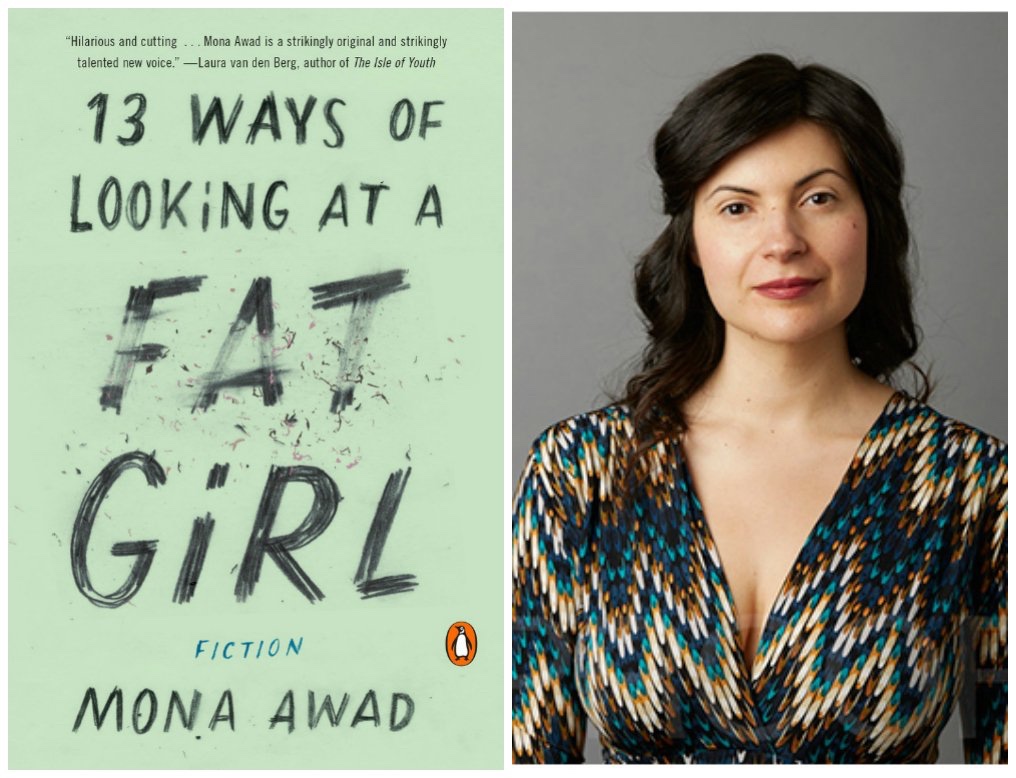

I don’t often re-read a book and when I do, I re-read it so I can savor the qualities that alerted to me what writing can provide for a reader, and in some instances, change a life. Seven years ago I read, “13 Ways Of Looking At A Fat Girl” and what stayed with me is a bold impression that author, Mona Awad, captures something that challenges female zeitgeist, in this case, beauty myths. For this re-reading of “13 Ways Of Looking At A Fat Girl” and due to stacks of reading projects, I opted for the audio version which was enjoyable especially since I don’t listen to many fiction audio books. Does this count as re-reading though?

Awad challenges beauty myths when she considers that thinness and all of its trappings. Awad dramatizes for readers how thinness offers potential guarantees for perceptions of beauty, access to social or professional groups, opportunities for visibility and relevance and discoveries of personal truths or definitions of self. In this case a girl sees herself as fat and no matter what changes she endures continues to see herself this way.

In this issue of Bookisshh we’ll take a look at a work authored by Mona Awad that employs laughter and pain while telling the story of a young woman growing into adulthood and who struggles with body dysmorphia and identity. Readers can learn how formative years do happen in youth and correcting maladaptive thinking for some is a lifelong challenge.

Please note if you are at all sensitive to this topic do take care and decide for yourself whether this is appropriate for you to read. The intent here is to do no harm, but instead look at how an author can normalize popular thinking and activate conversations in connection to body dysmorphia and identity struggles. Work like Awad’s is critical because it breaks the silence, is real and offers physically marginalized and/or psychologically conflicted options to be included in dignity, group membership, personal intimacy, professional success and plain old feeling good.

Thirteen Ways Of Looking At A Fat Girl begins with Lizzie who during high school and seeks male attention as a form of validation. Unfortunately, due to Lizzie’s hyper awareness of her body size and how this doesn’t coincide with what her teen peers value Lizzie makes poor personal choices. Lizzie only meets with boys on the sly who climb in and out of her window at night or picks up strange men on social dating/hookup apps. As a parent I found this horrifying, but I’ve been informed that high schoolers seek this as an option with some frequency since gaining social access and/or acceptance are difficult when one is perceived as heavy. The title points to 13 ways of looking at the self and are represented by 13 different times over Lizzie’s lifetime during which she struggled with her body always feeling too fat or not thin enough to sustain a relationship, gain an opportunity, or even be the apple of both of her divorced parents’ eyes.

Throughout Lizzie’s lifetime as her body changes, fat-to-thin and thin-to thinner, she changes her name to Elizabeth, Liza, Beth, etc. to facilitate her fresh start in a new iteration of her body. Some of these scenes are entirely uncomfortable for both reader and Elizabeth. Readers witness Elizabeth’s mother’s attention and the parading of Elizabeth and her athletic, thin, sculpted physique in front of her mom’s male, work counterparts while going to bars and clubs. Even at a more secure time in the life of Elizabeth readers watch a scene at the ice cream parlor when Elizabeth’s husband knows Elizabeth would enjoy his unfinished scoop. When her husband offers his last bites to Elizabeth, he confides his regret for doing so, and expresses hope that what usually occurs later—Elizabeth’s shame and resentment for indulgence— will not happen, but does and erodes their marriage completely. Just because Elizabeth’s body changes does not guarantee to Elizabeth, that her psyche will follow along this course. It’s painful to read how formative a person’s perceived flaws can shape and color their entire life even when there’s comedy.

Awad dramatizes women at a breaking point during which sacrifices over small things become life/death matters. Awad peels back the pain and suffering women endure to stay thin in order to be accepted, respected, and become part of collectives that vet and accept members based on their outward appearances. Elizabeth is symbolic of the Everywoman, who represent many women who have gone through one stage or another in the 13 ways Elizabeth is seen throughout her lifetime. In writing a book like this Awad raises awareness and hopefully someone going through this trauma and distortion can find their way to support. Adding identified support systems might be beneficial to add in the acknowledgements of this book. There are none to date.

With respect to Awad’s collective works, the potential for conversation centered around body, identity, and social participation are invigorating and challenge narratives, ways and mores practiced by many people. Awad interrogates the splendor and horror being female can offer and using humor and levity she provides kindness and a sense of relief, which is a benefit to all. I will likely read and cover Mona Awad’s collective works because it’s in the aftermath and recollections of her work I am reminded of how unique and essential her writing is even if it can make one uncomfortable—the truth does this doesn’t it? Enjoy!