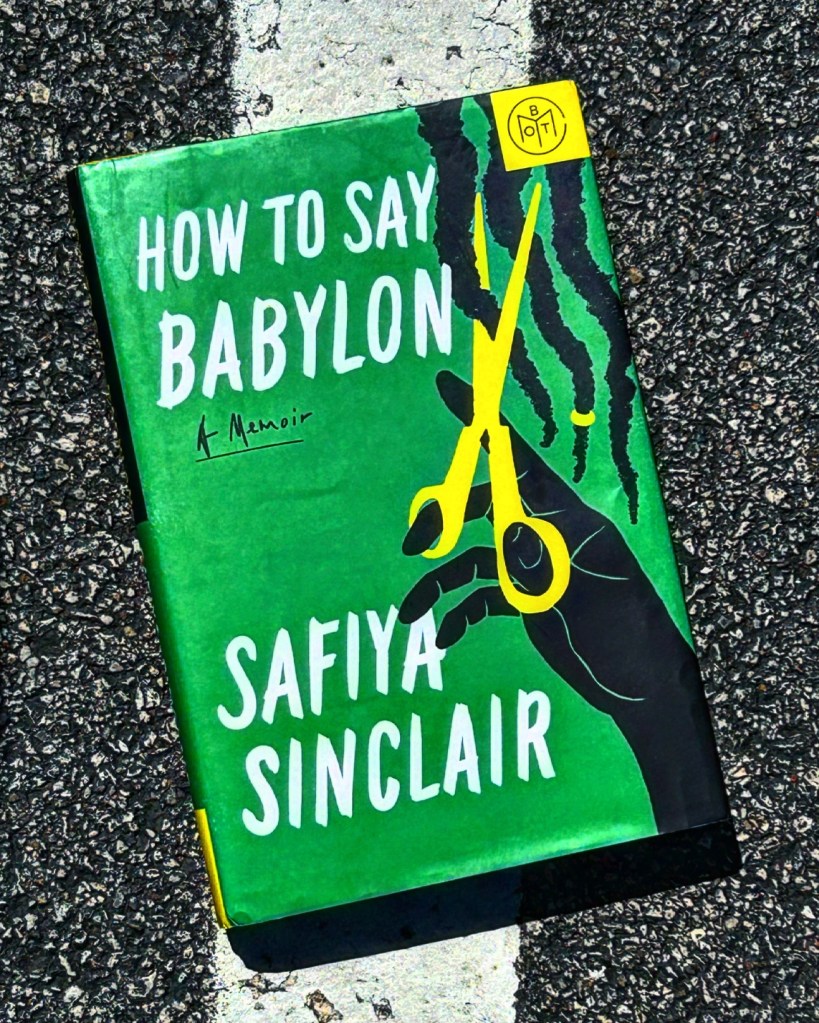

Happy May reading people! One might think that after I read the Women’s Prize for Fiction 2023 shortlist that I wouldn’t undertake a project of this sort again. Well I have, and in fact, 2 projects. My current aim is to read the 2024 inaugural Women’s Prize for Non Fiction AND the Women’s Prize for Fiction shortlists and determine my own winner or agree with the esteemed judges. Please note—this type of reading requires strategic shopping because most of the books are written by international authors and physical copies are not necessarily locally available in the United States.

How To Say Babylon is the second work I’ve read from the 2024 Women’s Prize for Non Fiction shortlist (Doppelgänger by Naomi Klein was the first work I read). Three words describe Sinclair’s memoir: Tragic, Beautiful and Redemptive. I mean wow…

So what’s it about? Sinclair begins her story in Jamaica and is the first born unto her parents. Both of Sinclair’s parents have previously lost or have become estranged from their mothers. Additionally, both of Sinclair’s parents had poor relationships with their remainder families and these experiences are submerged deeply into their consciousnesses and like a cancer, invade the raising the next generation.

When building their next generation nuclear family, Sinclair’s parents turn to Rastafarian beliefs and practices to give order and meaning to their lives. However, Rasta beliefs are taken to extremes and as Sinclair’s father hides behind secularism he turns his household into a micro-cult dominated by extreme patriarchal dictates regarding women, their role and function under the rule of men. The Rasta volume is on high and the environment is aggressive and oppressive. We’re talking trad wives without any increment of privilege or performative joy. It’s more like survivor with no audience and poverty without social safety nets…

Using first person point of view Sinclair chronicles her story of being born on the still colonized island of Jamaica and reveals how very few own their land and/or home. Sinclair pulls back the curtain revealing how islanders live in poverty even if they are fortunate to work in the tourist resorts. The quality of life for indigenous islanders is sub par and for this they look to and blame Babylon. The sacrifices for participation involve abandoning language and tradition and the resentments toward this set of alternatives run high, and so people are segregated into islanders, tourists and expats and you can pretty much figure out which two groups are thriving.

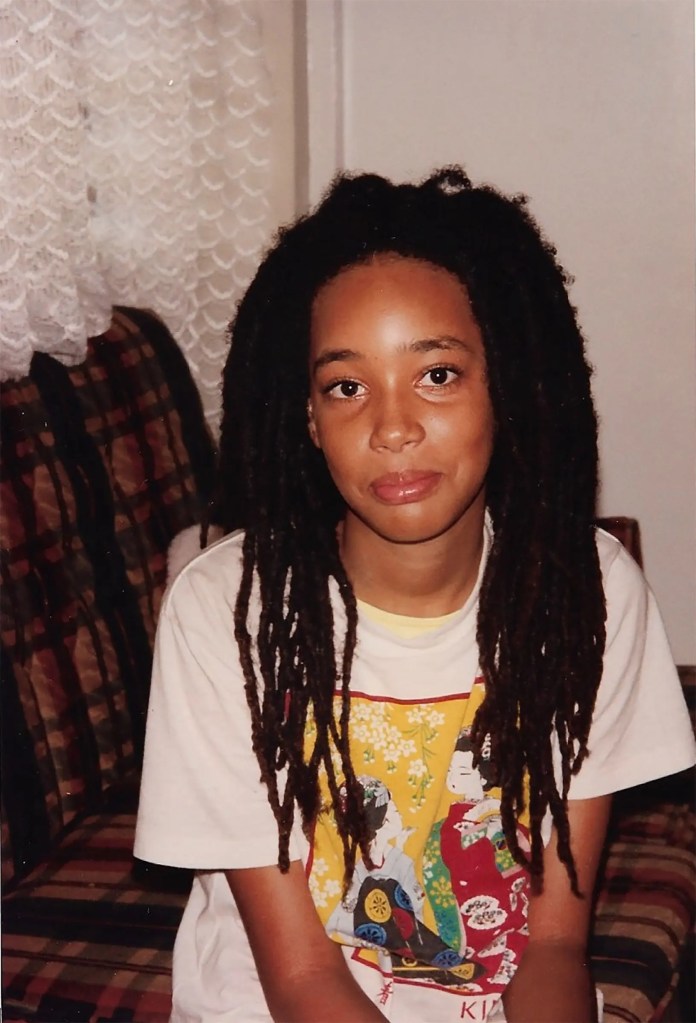

Readers follow Safiya’s life beginning before birth and all the way into her 20s. Readers witness her going from being the light of her father’s eye to becoming the shadow in his conscience. We watch her education from elementary education all the way through high school in Jamaica. We see her smile become marred by a terrible accident and watch her transform into becoming a model. As Sinclair’s life advances her freedom recesses and it is this contrast in Safiya’s life that births powerful poetry that startles the soul.

Sinclair’s family expands and as more children are born they move from place to place to either escape Babylon or to keep the evil eye off of them thus invading their privacy. Babylon is another word for colonial institutions as they flow into sociocultural and economic infrastructures. This is also referred to as “Whiteness.” Safiya’s father rebukes whiteness in all of its expression especially as it impacts his wife and children’s livity (or wholeness of life in its purest state). Safiya’s father runs his household on a very simple set of rules; strict observance of vegetarianism, reverence to Jah, complete purity of livity, smoking marijuana to be closer to Jah, submission of women to men, never cutting ones hair and growing dreadlocks. There is so much abuse in this book—I had to take breaks, but I promise you dear reader Sinclair and family does prevail though not without emotional scars..

The book explores the complex way that Sinclair’s mother is able to live 3 lives at one time: submissive wife, loving mother and skilled educator. Sinclair examines her struggles to become her own person due to an oppressive home life governed by Rastafarianism and her passion for and development of her poetry. Sinclair is the top of her class for her entire ex-pat education and when she graduates is mentored by an old poet who edits a prestigious Jamaican publication. Through this apprenticeship Sinclair’s work is celebrated by institutions and universities on the island as well as the United States.

For Sinclair, Jamaica is always calling both literally and figuratively. Sinclair wishes not to return but ultimately is pulled to move back and confront her demons still alive and plaguing her life. Uniquely, Sinclair uses her prose to bring ancient ancestry through to today in her musings, observations and painful recurrent memories using the landscape and people who populate the island of Jamaica.

A good example of demonstrating historic conflicts are demonstrated below. Sinclair describes the act and reason for her mother’s cutting of her dreadlocks.

Those dreadlocks had been growing on my mother’s head since she was nineteen years old and living in a Rasta commune deep in the hills. They had grown pas the birth of four children, two miscarriages; countless unnamed students laying their sticky palms upon her head; through my father’s so-called friends Mama Lee and Reina and Primrose. They had outgrown decades of changing presidents and prime ministers, had mourned the death of Bob Marley and Peter Tosh and Dennis Brown, and had kept on growing through plane crashes, economic crashes and multiple space shuttle crashes. They had seen the coral reefs by her seaside village vanish, and had weathered the death of her own father. Those locks had held and comforted and aided the mass mutiny of her daughters, but it was the cutting of her own womb that finally made her do it.

So much history is woven into the different dreadlocks of each family member and Sinclair gives glimpses of this emancipation from the past which unfortunately was quite painful for the family members who took to scissors and cutting of dreadlocks. If only releasing the past was this easy as the painful past might be gone, but the memory and trauma is haunting and the best one can hope for are coping mechanisms, or better yet live well.

Could How to Say Babylon be the winner of the 2024 Women’s Prize for Non Fiction? Yes! Though I’m 2 for 2 on this shortlist of 6 this book takes 1st place so far. 4🖊️🖊️🖊️🖊️ out of 5. Sinclair isolates her narrative on her family, Rastafarian impact, feminist plights and the restrictiveness migrant people endure. As Sinclair examines and reveals these themes, she leaves out other themes—emotional intimacy, dating, her actual education and transactions that promote growth and challenge Sinclair. It felt like some things were missing that are potential explanations of a full lived life. Compensatory for this lack of livity granularity is how absolutely beautiful Sinclair is at the sentence level. Her prose is expansive, transformative and luminous. A gorgeous poet Sinclair is indeed.

It’s a memoir, life goes on, Sinclair lives to tell her tale and becomes a poet and author. The family reckoning, however, I won’t disclose because it is entirely worth reading. Enjoy!